It’s not easy to live up to your name if you’re named “Light of the Faith”. Nur ad-Din Zengi did a fine job at that, though.

Nur al-Din Mahmud Zengi, often spelled as Nuruddin Zangi, was from the Oghuz Turkic Zengid dynasty. An important figure leading the defences against the Second Crusade, Nur al-Din Zengi reigned for a little under three decades, from 1146 to 1174 CE.

Nur ad-Din Zengi — Standing Against the Invaders

The Second Crusades and the subsequent Crusader Invasion of Egypt were a tumultuous period in history. Backed by religious zeal, the Crusaders repeatedly launched attacks on Muslim heartlands, seeking to capture territories right, left and center. Many Muslim leaders, rulers and heroes rose to the occasion, leading the defence against the Crusaders across all fronts.

Whilst the role of the likes of Sultan Saladin is well-known in the later part of the Crusades, there are many heroes that Muslim chroniclers often tend to overlook. One such name is Nur ad-Din Zengi.

Right after the death of Imad ad-Din Zengi, his sons, Nur ad-Din and Saif ad-Din divided the kingdom among themselves — the former stationed himself at Aleppo whereas the latter chose to be in Mosul. This was in stark contrast to what many Muslim sultanates, emirates and kingdoms would often see — there was no war of succession or mutual rivalry between the brothers. Compare this with the wars of succession fought between princes of the Ottoman Empire, or the Mughal Empire, and you’d see how devoted Nur ad-Din and his brother were to their cause.

The Start of Conquests

As soon as Nur ad-Din came to power, his primary motive was to ensure no further lands are lost or cities are destroyed at the hands of the Crusaders. He made multiple attempts to reach out to other Muslim states of the region, seeking alliances against the Crusading invaders.

Nonetheless, Muslim history is marred by a lack of mutual trust and unity between rulers and leaders. Nur ad-Din Zengi’s times were no different. Case in point: despite having a matrimonial alliance with Nur ad-Din Zengi, Muin ad-Din Unur, the Governor of Damascus, was reluctant to upset the Crusader states and often apprehensive of Zengi’s intentions.

In spite of it all, Nur ad-Din Zengi managed to capture multiple key prospects in Asia Minor. By the time the Second Crusade led by Conrad III of Germany and Louis VII of France got there, Nur ad-Din successes had ensured that there was very little they could do to reclaim lost territories. The Crusaders attempted a failed siege of Damascus, following which Nur ad-Din Zengi decided to push further towards the West. Things came to a face-off in the Battle of Inab, when Nur ad-Din Zengi destroyed the combined forces of Prince Raymond of Poitiers and the Nizari Assassins of Ali ibn-Wafa. Following the Battle, Nur ad-Din marched all the way to the coast, symbolically bathing in the Mediterranean Sea, to assert his dominance of Syria.

Nur ad-Din Zengi in Syria

The big question is: why would Nur ad-Din Zengi need to establish dominance in such a way? The answer is not hard to find.

Right after the First Crusade, the Muslim rulers of Damascus had entered into bilateral treaties with the Crusaders. However, the “bilateral” part was mostly on paper — the Crusaders, ever-keen on expanding their territories, launched the Second Crusade, despite the peace treaties being in effect.

The rulers of Damascus, Muin ad-Din and his successor Mujir ad-Din, were less than ready to confront the Crusaders for their unkept promises. In fact, Mujir ad-Din went as far as paying an annual tribute to the Crusaders to save his seat in Damascus. Such was the animosity against his policies of submission that the population of Damascus rose against Mujir ad-Din, and aided Nur ad-Din Zengi in taking over the Syrian region.

This is primarily why Nur ad-Din Zengi had to assert his control over Syria. To keep the Crusaders in check, such actions were necessary.

The Case of Egypt

Routed in Syria and the north, the Crusaders had very little to gain there. As such, they turned their attention towards the Fatimids in Egypt. Whilst the nominal ruler of the Fatimids, al-Adid, was in power in theory, the Grand Vizier Shawar ibn Mujib al-Sadi was the de facto ruler.

Fatimids, being weak and leaderless, were no match when the Crusaders led by King Amalric I of Jerusalem attacked. Egypt fell quickly, and Shawar approached Nur ad-Din Zengi for assistance. Nur ad-Din was unsure about sending his troops to Egypt and leaving Damascus defenceless, but was persuaded otherwise by his general Asad ad-Din Shirkuh, the uncle of Saladin Ayyubi.

Asad ad-Din Shirkuh made quick gains in Egypt, routing the Crusaders yet again from Muslim lands. However, it was at this juncture that Shawar, the ousted Grand Vizier of Fatimids, revealed his true intentions. He allied with King Amalric I, and effectively betrayed the Zengid forces led by Shirkuh.

As soon as Shirkuh returned from Egypt, Shawar got his dues — Egypt was declared a vassal state by the Crusaders and Shawar was rendered a mere puppet.

Eventually, Shawar’s son Khalil requested Nur ad-DIn Zengi for assistance yet again, and when Asad ad-Din Shirkuh arrived, this time there were no betrayals to be made. Egypt was reclaimed, and Shirkuh was established as the Grand Vizier of Egypt. Eventually, he would be succeeded by Saladin the Great.

Legacy

Nur ad-Din Zengi died in 1174 CE at the age of 56. While he had seen Egypt and Syria accept his authority, it was only when Sultan Saladin effectively brought the lands under one crown in 1185 that Nur ad-Din Zengi’s dream was fully realized.

A lot can be said about the military career of Nur ad-Din Zengi. An able commander and a skilled statesman, he left no stone unturned in his quest against the invading Crusaders.

But what about Nur ad-DIn Zengi as a person? Thus writes William of Tyre, stating that Nur ad-Din Zengi was

…a just prince, valiant and wise, and according to the traditions of his race, a religious man.

Nur ad-Din was an epitome of religious tolerance. When Baldwin III, the king of Jerusalem died, it was expected that the Zengids would lead an attack on Jerusalem, taking advantage of the weakened situation. However, Nur ad-Din Zengi decided otherwise, claiming:

We should sympathize with their grief and in pity spare them, because they have lost a prince such as the rest of the world does not possess today.

Unfortunately, such gestures were not always reciprocated. Right after the death of Nur ad-Din Zengi, Amalric I of Jerusalem immediately launched an offensive, and extorted vast amounts of money from Nur ad-Din’s widow.

Nur ad-Din Zengi gave equal rights to the Christians and other non-Muslims living in Zengi-ruled territories. In fact, it was not the Crusaders or Christianity in itself that he was fighting against — he was displeased by the looting, marauding and plundering that Crusading armies would indulge in. He regarded such actions as profanities, and was determined to put an end to it.

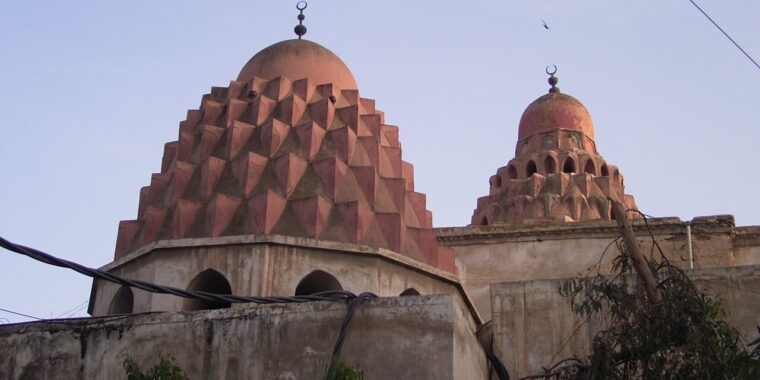

Nur ad-Din constructed over twenty Madrassahs from his personal funds. He held a Diploma in Hadith Narration, and scholars such as Sir Steven Runciman have described him as a ruler who prioritized justice over everything else.

Appraisal

It is unfortunate how little is known to the Muslims learners of today about the life of Nur ad-Din Zengi and his contemporaries. Whilst the later rulers, such as the Ottomans and the Mughals, are often romanticized owing to television and web series narratives, the painstaking efforts that early-medieval leaders took to keep the flame of Islam and social justice alive are oft-forgotten.

With that said, Nur ad-Din Zengi was a great figure and a person of exemplary courage, modesty and piety. May Allah be pleased with him!

References

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster.

- Barber, Malcolm (1994). The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple. Cambridge University Press.

- Runciman, Steven (1952). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God’s War: A New History of the Crusades. Harvard University Press.

- William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, trans. E.A. Babcock and A.C. Krey. Columbia University Press, 1943.

Featured Image: Domes of the Nur ad-Din Zengi Madrassah / Wikimedia Commons

A version of this article appeared in Muslim Memo.